The Poop-Pile Time Capsules of Range Creek Canyon

Reposted from the Natural History Museum of Utah’s Science Stories blog.

Where some might see a humble mound of rat poop, Marti Sorensen sees a valuable ecological record. The piles, called middens, contain more than just feces; they’re built over dozens of years by pack rats as the rodents accumulate bits of plant debris and other refuse. Middens preserve well—some are thousands of years old—which means they often hold tiny fossils that researchers can excavate. They’re particularly useful in arid places, where vegetation is sparse and water is scarce.

“The plants and animals that are surviving there are so evolved and adapted to living in such a harsh environment. It’s beautiful to see that there’s actually so much going on there,” said Sorensen, a paleoecologist at the University of Utah. She works with pack rat middens in Range Creek Canyon, aiming to piece together a history of the canyon’s vegetation and climate. The project has been in the works since 2005, but Sorensen joined in 2022 as an undergrad student during a summer research program. She is continuing on the project for her graduate studies in the U’s School of Environment, Society & Sustainability.

Utah’s pristine archaeological preserve

Located in eastern Utah on the southern edge of the Tavaputs Plateau, Range Creek Canyon holds countless examples of a rich archaeological history, such as granaries, dwellings and rock art. Under an agreement with the federal Bureau of Land Management, the Natural History Museum of Utah manages a field station in the canyon, which is used in collaboration with interdisciplinary experts from the University of Utah. From around the years 400 CE to 1200 CE, the canyon was occupied by people of the Fremont culture before they vanished. Archeologists aren’t sure why the inhabitants left the canyon and, shortly after, the Great Basin. Rat middens can reveal some clues about the Fremont people’s lifestyle, such as their agricultural practices. While Sorensen’s work focuses on the height of their occupation in the canyon, it also examines the broader ecology of the canyon over the last 9,000 years.

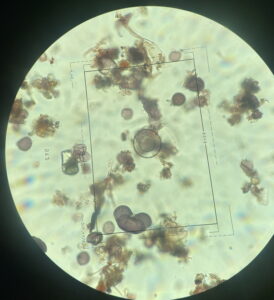

One way that paleoecologists study ecological history is through fossilized pollen grains. Different types of plants have unique pollen structures, which can be seen under a microscope. That means researchers can determine the kinds of plants growing in an area in the past by looking at ancient pollen. They can also do this with macrofossils: bits of preserved plant pieces, insect parts and bone fragments that can be observed without a microscope. For pollen and plant matter to persist as fossils, instead of decomposing, they need to land in the right conditions. Anoxic—or oxygen-poor— environments are ideal, Sorensen said. Researchers often turn to mucky sediment cores for plant matter preserved in this way, such as from lake shores or bogs. But Range Creek Canyon has few continuously wet areas.

“That’s where the pack rats come in,” Sorensen said. “Their fecal matter essentially encases the plant materials and preserves them, so it creates those anoxic conditions that the bog cores do.”

Curated by rodents, preserved in pee

Scientists have used these poop-pile time machines for decades. Pack rats form their middens communally over many generations. They bring leaves, seeds, bones and other debris—including garbage from humans—into the pile, defecating and urinating as they go.

“Pack rats are an animal that never drinks water their entire life,” said Sorensen’s adviser, the U paleoecologist Larry Coats, an associate professor of geography. “They get all of their moisture from vegetation, and so their urine is really super viscous. And when they pee on these piles, that just permeates it and basically solidifies it and just seals it off in the environment.”

For her master’s thesis, Sorensen examined microscopic pollen grains and macrofossils—biological objects large enough to see with the naked eye—from 45 pack rat middens throughout Range Creek Canyon.

Finding the middens was a collaborative effort started by Sorensen’s mentors and colleagues two decades ago. A good place to look for ancient middens is under rock overhangs, where they are protected from rain and weather. Some middens hide in crevices within cliff faces, accessible only by rope.

After collecting samples from the middens, the hardened urine and feces needed to be dissolved to reveal the fossils inside. Macrofossils could be picked from the sludge using a screen, while the pollen grains required a few more steps for retrieval. Once the fossils were separated, the team dated pieces of vegetation—mainly conifer and juniper needles—to determine the middens’ age. The youngest was around 100 years old, while the oldest was more than 9,000 years old.

Snapshots of the past versus a continuous record

This research had two goals. First, Sorensen sought to discover how the fossilized vegetation in the piles compared to the fossilized pollen. She also explored how the pollen record in the middens stacked up to the pollen record from sediment cores taken from bogs on the canyon floor.

“You have two different kinds of records. With pack rat middens, what you have are snapshots of just one time period that’s bracketed in the radiocarbon age,” Coats said. “And with the sediment cores, you have a continuous record from the top that’s the present down to whatever depth of age you’ve got. They complement each other. So now what we can see is change through time where we might have a gap in the midden record.”

Sorensen found that among plants adapted for dry conditions, the pollen record mirrored and the macrofossils. Middens showcased local vegetation, while the sediment cores reflected regional plants with airborne pollen and wetland plants. Sorenson’s findings, outlined in her master’s thesis but not yet published in the scientific literature, also highlighted a bump in aridity in the mid-Holocene, around 6,000 years ago, evidenced by a shift toward drought-tolerant plants.

“Marti’s biggest contribution, so far, has been to tie the pollen very specifically to our suite of species so that we really have a double signal,” Coats said. “Instead of just a pollen signal for one thing and a macrofossil signal of something else, we really have a double signal of what’s going on with species in the canyon.”

Now working on her doctorate in geography, Sorenson plans to explore those shifts more by looking at seasonal plant patterns stored in the middens. That can help answer questions about the climate in the canyon and how it changed over time. She also plans to look for relationships between the plants and pollen found in middens and their proximity to archeological sites.

In addition to Coats, Sorensen expressed gratitude to her other mentors at NHMU and the U’s School of Environment, Society & Sustainability, including Shannon Boomgarden, who directs the Range Creek Field Station; Andrea Brunelle, director of the RED Lab; and Mitchell Power, curator of botany at the museum’s Garrett Herbarium.

The author, Jude Coleman, is an Oregon-based science journalist who writes about the environment, ecology, and humans—sometimes all three at once. Banner photo shows Lighthouse Canyon, part of Range Creek Canyon in eastern Utah.

About the Blog

Discussion channel for insightful chat about our events, news, and activities.